Fighting for Indigenous Rights: How ESG Helps Make the Case

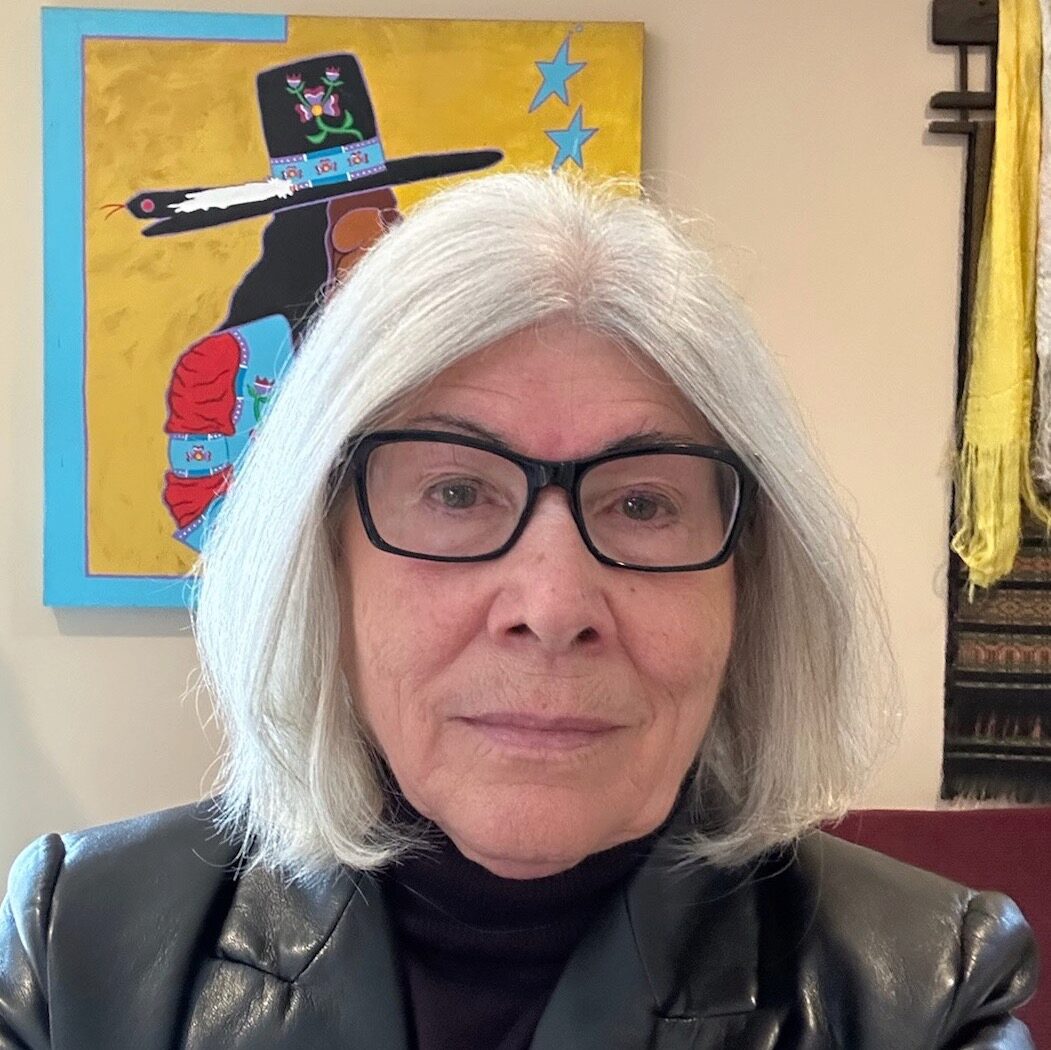

Cherokee economist Rebecca Adamson has partnered with Wharton’s ESG Initiative to support research on the social costs of development on or near indigenous land. She said stakeholders need truthful, accurate information as native populations across the globe are under increasing pressure from development.

Cherokee economist Rebecca Adamson spent years trying to find a scholar who could measure the risks of investing in development projects on or near land held by Indigenous people.

“If you’re an Indigenous person, you don’t have a lot of choice in not trying to continually defend this space of who you are and your culture and how you live.”

– Rebecca Adamson

As both an activist and entrepreneur, she knows the challenge. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks are difficult to quantify because there is no single set of standards or widely accepted methodology. The prevalence of greenwashing and public relations spin leads to what she calls “management by headlines,” where the information presented to stakeholders and shareholders doesn’t match reality, and decisions are made blindly.

But her work to reroute the Dakota Access oil pipeline away from the drinking water supply of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s reservation in North Dakota proved to her that people pay closer attention when risks are translated into concrete numbers.

“We’ve seen that someone who performs poorly with Indigenous rights performs poorly with their whole social profile,” Adamson said. “You can’t argue with the evidence.”

That’s why she needed someone who could do it right. She met with scholars around the country, finding some who had the interest but not the ability, and others who had the ability but not the interest.

Then she met Witold (Vit) Henisz, vice dean and faculty director of the ESG Initiative at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and Deloitte & Touche Professor of Management in Honor of Russell E. Palmer, former Managing Partner. From their first conversation in 2019, she was hooked.

“I’m used to communicating to an Indigenous constituency, nonprofit allies, and the public. I didn’t want to talk wonky finance and research — Vit does that,” she said with a laugh. “But I would throw it out in plain talk, and Vit could pick it up and build it out.”

Impressed by Henisz and his pioneering research on ESG, Adamson went back to the board for a grant to expand the professor’s study on the impact of financing large infrastructure projects near indigenous land.

“The closer you were to indigenous lands, the more likely you were to be sued, to be called up for regulatory inquiry, or be challenged with labor strikes or slowdowns.”

– Witold Henisz

“We found that there was this really striking relationship,” Henisz said. “The closer you were to indigenous lands, the more likely you were to be sued, to be called up for regulatory inquiry, or be challenged with labor strikes or slowdowns. Those all have costs associated with them. We were able to show this correlation between proximity to indigenous lands and these material outcomes.”

That grant led to more support from the Bay and Paul Foundations and the Christensen Fund. In total, Adamson has helped raise more than $1 million toward research on political risk and human rights at Wharton. Some of that money is being used to create a data-driven index of risks faced by companies investing on or near indigenous land around the world.

To honor her, the Wharton School will name the online repository as the “Rebecca Adamson Indigenous Rights Index (RAIRI).”

Adamson, who also serves as an adviser to the ESG Initiative, said she’s humbled by the recognition, but it’s the work that matters most. Indigenous communities are under tremendous pressure from development projects that too often do not benefit the people who live there. In fact, Adamson said, those projects typically result in an acceleration of poverty, violence, and health dangers for already vulnerable Indigenous populations. Numerous studies back up that assertion, including ones from Henisz currently under review that found projects near indigenous land that are funded with foreign direct investment usually entail conflict, as well as development projects near UNESCO World Heritage Sites. These sites have enormous potential value as tourist destinations but that value can be undermined, or even turned into value destruction, by conflict.

“This is the last land grab. We’ve got 30% of the remaining land, and 80% of the remaining biodiversity, and they want it.”

– Rebecca Adamson

“This is the last land grab. We’ve got 30% of the remaining land, and 80% of the remaining biodiversity, and they want it,” Adamson said. “I’m not saying no development. I’m saying you’ve got to work with us and get this right. We will continue to take care of the land, but we should derive the benefits from the markets.”

The work also matters to Henisz, an interdisciplinary professor of management who makes the business case for ESG. He shares a similar background with Adamson in political and social risk management for natural resource and infrastructure projects and has worked extensively with corporations on those topics. He said the “S” in ESG is garnering more attention these days, so more research is critical.

“What we’re trying to do is similar, and I think that’s one of the reasons we hit it off,” he said of Adamson. “You can think of it as two overlapping Venn diagrams, but I think of it as parallel journeys. She’s been a change agent, a leader, and a heroine on the side of justice. And I’ve been trying, in my role, to support the system-level change that people like her are working towards by highlighting the financial arguments for monitoring and mitigating indigenous rights risks.”

A Life of Service

Adamson was born in Akron, Ohio, in 1949 and spent her childhood summers with her Cherokee grandmother, learning about her native history and culture. As a young woman in the 1970s, Adamson became known for her work to end the 100-year-old practice of forcing Indigenous children into boarding schools operated by Christian missionaries and the federal government. Native children were prevented from speaking their languages and were subjected to abuse and violence.

During her first five years with the Coalition of Indian Controlled School Boards, Adamson was frequently arrested for her protest activities. But her steadfastness led to the passage of the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, giving tribes greater autonomy over public services.

“I was thrown in and out of jail for the first five years, and now I’m an adviser to the Wharton ESG Initiative. I always like to tell young people that when they ask me about my career,” said Adamson, 74.

The years in between were filled with hard-fought accomplishments. Adamson founded the First Nations Development Institute, which created the first microfinance fund in the country. She then founded First Peoples Worldwide, which provides hundreds of grants to Indigenous communities in over 60 countries. She joined Calvert Social Investment Funds, where she led their community development financial institution (CDFI) and developed the impact investing vehicle, Community Notes. She was an adviser to the United Nations, the Obama administration, the Catholic Conference’s Campaign for Human Development, and the World Bank.

Adamson’s work has taken her from the U.S. to Australia, Botswana, Namibia, and other parts of the world where Indigenous communities are threatened. She’s won numerous awards and accolades, including being named a PBS Change Maker and one of the 1997 “Women of the Year” by Ms. magazine. She counts the magazine’s founder, Gloria Steinem, as a friend.

These days, Adamson lives on a 100-acre farm outside Fredericksburg, Virginia, with her husband of four years, John Guffey, W’70, co-founder of the Calvert Social Investment Fund and a Wharton grad. They knew each other as friends and colleagues for decades, while they were both married to other people. Adamson’s first husband died in a hunting accident, and she lost her second husband to cancer. John’s first wife also passed away. Adamson jokes that she and Guffey are the “grandma and grandpa” of social impact investing. “In my culture, I would say we’re the elders.”

When asked what keeps her going in the face of such daunting work, Adamson is careful to avoid hyperbole. For her and her people, it’s about survival.

“If you’re an Indigenous person, you don’t have a lot of choice in not trying to continually defend this space of who you are and your culture and how you live,” she said. “With that at my core, I’ve been able to keep myself energized and keep pushing.”

That persistence is what led her to Wharton, where she found a like mind in Henisz and his colleagues. She’s hopeful that their work in quantifying social costs will bring those concerns to the fore, especially for investors.

“Environmental costs have always been way ahead of social costs, and I’ve been trying to prove that social risks are as expensive as environmental risks,” she said. “We need to move forward on a lot of fronts, but to actually change behavior, we need to follow the money.”

By Angie Basiouny