Given the decades-long trend in rising disaster costs and the increasing number of high-cost events, policymakers are increasingly looking for ways to reduce the financial impact on taxpayers. This is especially critical as climate change alters the frequency and severity of extreme events and as Congress increasingly relies on multi-billion dollar off-budget appropriations to cover disaster costs. FEMA has (unsuccessfully) tried to reduce federal costs by shifting more of the burden back to state and local governments through a “disaster deductible.” That proposal was met with resistance from some stakeholders, with opponents arguing that it would be too confusing, expensive, and bureaucratic.

To effectively reduce federal exposure to disaster losses and simultaneously encourage local governments to better manage their risk and invest more in cost-effective risk reduction measures, FEMA should widely eliminate assistance for the repair and reconstruction of public buildings, exempting small and financially challenged communities that would not otherwise recover.

The vast majority of FEMA disaster assistance is directed to state and local governments through the agency’s Public Assistance (PA) program. The PA program must be authorized by a presidential disaster declaration, after which point FEMA can begin disbursing funds to impacted communities. PA funds are used for two categories of expenditure: emergency and permanent work. Emergency work includes debris removal and emergency protective measures like flood fighting, slope stabilization, and search and rescue operations. It is carried out immediately prior to and after a disaster to protect lives, property, and public health. Permanent work, however, is focused on long term recovery and is used to help restore public facilities to their pre-disaster condition. Permanent work funds are used to repair or replace public buildings and equipment, roads and bridges, water control facilities, utility facilities and infrastructure, and parks and recreational facilities.

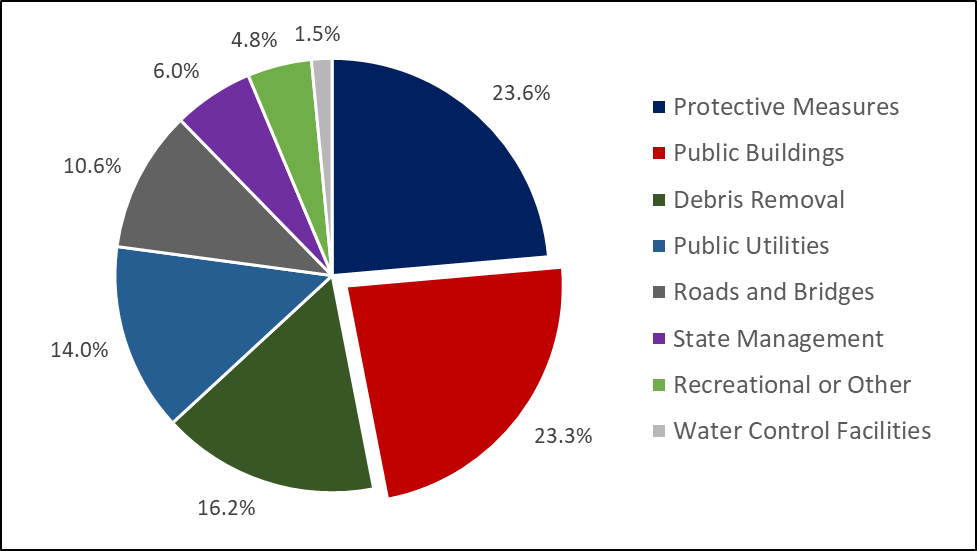

Among these various authorized expenditures, FEMA spends more on public buildings and emergency protective measures than other PA categories. From 2000 to 2018, FEMA spent roughly $95.5 billion (in 2018 dollars) on PA. Approximately $22.6 billion was dedicated to emergency protective measures and another $22.3 billion to public buildings. The table below shows the distribution of PA spending from 2000-2018.

FEMA Public Assistance Grants by Category of Work (2018 USD)

Source: Made by the author with publicly available FEMA data

Funding emergency work can be a critical federal role, helping save lives and minimize disruption, particularly in low- and moderate-income communities that may not have enough savings to pay such costs on their own. However, the rationale for federal dollars being use to repair public buildings – known as Category E Public Assistance – is less clear. Category E funds essentially provide free insurance coverage for state and local governments. Public buildings could have been insured instead and then not needed federal taxpayer dollars for repairs. Requiring insurance for public buildings would also send a price signal to local governments about where and how to build safely.

Federal assistance may be justified for roads, bridges, utility poles, and other types of public infrastructure that are difficult and/or expensive to insure. But public buildings are insurable. The private sector has insured commercial structures for decades and the commercial buildings currently covered by the private sector are often very similar to municipal buildings. Insurers (including the National Flood Insurance Program) are willing and able to take on these risks. Yet, many communities continue to rely on public funds and forego coverage. Who wouldn’t want free insurance?

FEMA does have certain requirements in place to encourage communities to insure some of their assets. For example, as a condition of receiving aid for permanent work, PA recipients must purchase and maintain insurance for the type of hazard that damaged the building (for example, flood insurance would be required for a flood damaged building). Also, for uninsured or underinsured properties in the FEMA-mapped 100-year floodplain, PA grants are reduced by the maximum insurance payment that would have been received if the building and contents were fully covered by an NFIP policy. These rules aim to make grantees bear a greater share, if not all, of the costs in the case of future events. But according to the Inspector General for the Department of Homeland Security, they have not been adequately implemented.

As another way to force local governments to have a financial stake in the decisions they make about development in hazard-prone areas, PA recipients are generally required to contribute 25% of PA project costs. This also creates some financial incentive to reduce risk pre-disaster. However, in the wake of major events, local cost-shares are often waived or paid by other federal dollars, thereby removing these incentives.

Thus, Category E assistance is likely creating a moral hazard among many state and local governments who, because of their belief that federal funds will be available post-disaster, fail to effectively manage their risk ex ante. The availability of assistance discourages them from taking proactive risk management steps like purchasing insurance or investing in hazard mitigation.

This is especially concerning because, in foregoing such measures, state and local governments may be putting themselves in an even more precarious financial situation since there is not an actual guarantee they will receive assistance—just political precedent. PA is only available when the president issues a major disaster declaration and even then, there is no guarantee that PA funds will be provided. If no Category E funds come through, the community may be left with a damaged building and have to divert local tax dollars or borrow funds for its reconstruction. Slow funding and repairs could also inhibit local provision of essential services such as medical care or emergency services that would be especially critical if another disaster were to strike. In contrast, with insurance in place, funding would be much more certain and the community would receive funds more quickly, allowing them to get critical facilities up and running as soon as possible.

FEMA recognizes the value of insurance and the incentive problems Category E funds create. In their 2018-2022 strategic plan, the agency states: “financial preparedness discipline requires communities to understand and appreciate the risks to public buildings and facilities and to secure insurance to cover the cost of replacement.” That will not happen if Category E funds remain as widely available as they are today.

For these incentives to work effectively, however, the repair and reconstruction of insurable public buildings and equipment must be ineligible for all types of federal disaster assistance. (HUD’s Community Development Block Grant – Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program would also have to be examined for its impacts on local incentives as it has become an increasingly popular distribution channel for federal recovery funds.)

Eliminating Category E would have to be done slowly over time and proper notice must be given to states and communities far in advance so they can implement appropriate risk management schemes and effectively plan and budget for additional disaster costs. For communities or buildings where private insurance may be unaffordable, municipal insurance pools may be a viable alternative. Such pools already exist in every state to help cover uninsurable risks for local governments. These could be adapted so that local governments could mutually insure disaster damages to public buildings.

Eliminating Category E funds could help FEMA achieve many goals it had for the disaster deductible, including: encouraging state and local governments to better plan and budget for disasters; incentivizing hazard mitigation; reducing the costs of disasters and corresponding federal assistance; providing greater clarity on what assistance will be provided when; and make more effective use of taxpayer dollars.

Finally, this solution would not require Congressional action nor statutory changes. FEMA has the authority to implement it through the federal rulemaking process. They should do so thoughtfully and engage state and local governments, but make clear that the change is going to happen and that local decision-makers must do more to protect their communities from future disasters.

At the time of posting Brett Lingle was Policy Analyst and Project Manager with the Wharton Risk Center.