September 15, 2017

Senior Research Coordinator at Wharton Risk Center

Hurricane Harvey destroyed vital roads, public infrastructure, and hundreds of thousands of homes across Houston and southeast Texas. In Florida, Hurricane Irma has left communities reeling with widespread blackouts, severe coastal flooding, and crippled telecommunications systems. When floodwaters finally recede and the debris is cleared, recovery will be long. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) will be in these areas for years. And costs will reach well into the billions.

President Donald Trump has promised a swift and robust federal response. Congress passed legislation to provide an initial $15 billion to FEMA, HUD and the Small Business Administration (SBA) for disaster relief. And so far, 700,000 Texas residents have registered for federal assistance, with more than 50,000 placed in temporary housing.

As early damage estimates approach $200 billion across Florida and Texas, what will the federal government’s response look like? How will FEMA help communities and families in the coming months and years? And how much federal funding can the affected areas expect? Those questions are difficult to answer until the water recedes and damage assessments are completed, but FEMA’s response to previous hurricanes may provide some clues.

FEMA spends more on hurricane recovery than on any other type of disaster. Data from OpenFEMA indicates that of the $81.1 billion (nominal dollars) of post-disaster aid the agency has distributed from 2005 to 2016, 70 percent was for hurricane response and recovery. Severe storms and floods accounted for another 25 percent, and all other disasters accounted for just 5 percent.

FEMA delivers post-disaster assistance through three major programs: the Public Assistance (PA) Program, the Individuals and Households Program (IHP), and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP). The PA program provides funds to state and local governments for debris removal, emergency protective measures, and the repair and reconstruction of public facilities. IHP provides two types of assistance: Housing Assistance (HA), which goes toward the repair or replacement of damaged homes or temporary housing needs, and Other Needs Assistance (ONA), which may be used to cover disaster-related expenses such as transportation, medical expenses, funeral costs, or replacing personal property. Finally, HMGP provides funds for measures to reduce damages from future disasters. This includes actions such as implementing flood control projects, elevating homes, or buying out high-risk properties and preserving them as open space.

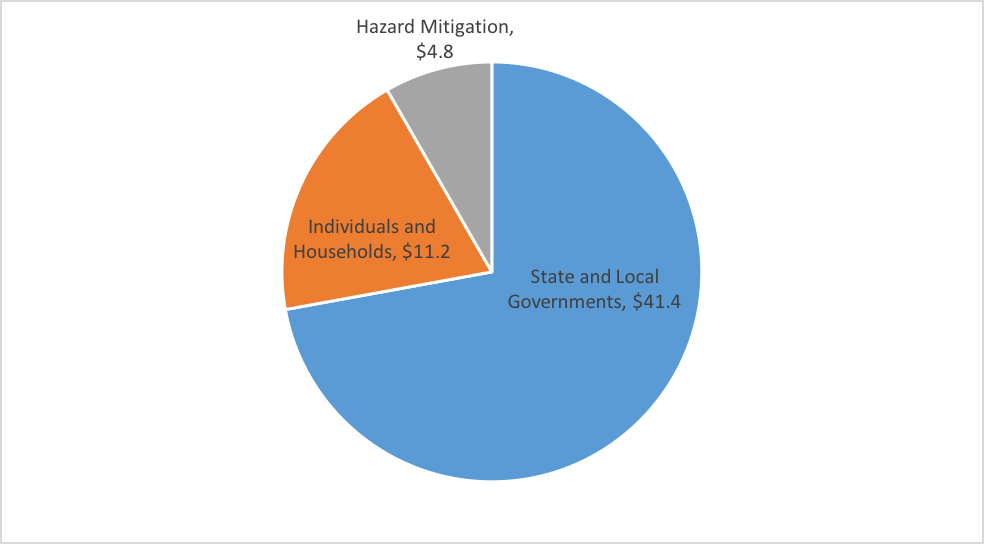

Since 2005, 72 percent of FEMA’s hurricane relief funds ($41.5 billion) have gone to state and local governments through the PA program. Roughly 20 percent ($11.2 billion) was provided to individuals and families through IHP, and another 8 percent ($4.8 billion) was provided through HMGP.

FEMA Disaster Assistance Obligations for Hurricane Recovery 2005-2016 (in billions of nominal dollars)

The largest single share of PA funds ($15.2 billion) was used to repair public buildings. Another $7.8 billion was used for emergency protective measures, such as flood fighting and search and rescue operations; $5.9 billion for public utility repairs; $5.7 billion for debris removal; and the remainder to repair roads and bridges, water control facilities, and recreational property.

Of the 20 percent of total funding that went to households, more than half went to rental assistance for displaced residents; 21 percent to help victims make their damaged homes safe and habitable (program requirements stipulate that HA repair funds may only be used to make a home “safe, sanitary, or functional” and are not intended to return a home to its pre-disaster condition); and 26 percent for ONA. In general, IHP is only available if an applicant cannot secure funds from another source such as insurance, charity, or loans from the SBA. Grants are currently limited to $33,300 per household, though my calculations suggest that the average grant, in 2016 dollars, is for just $5,500, which is likely not enough to cover a family’s disaster-related expenses.

Because insurance makes recovery funds available more quickly and enables victims to recover more fully (given sufficient coverage levels), it is a far more effective tool for meeting post-disaster needs. However, only 15 percent of households in Harris County, Texas have flood insurance. Estimates indicate that total residential flood losses from Harvey will range from $25 billion to $37 billion, with 70 percent uninsured. Given these low coverage levels and FEMA’s expectation that this will be “one of the largest housing recovery missions the nation has ever seen,” overall IHP spending for Harvey will likely be very high, possibly on par with Hurricanes Sandy ($1.5 billion) and Katrina ($6.5 billion).

HMGP, the last major tranche of FEMA assistance, is a function of the total relief FEMA provides under a major disaster declaration. HMGP funds have been used primarily for mitigation reconstruction (19 percent; building an improved, elevated structure where an existing building and/or foundation has been damaged), property buyouts (13 percent), and flood control measures (12 percent). Lesser amounts have been allocated to property elevations (5 percent) and measures to protect utilities and infrastructure (5 percent).

If history is any indication, the vast majority of FEMA’s resources will be dedicated to rebuilding public facilities and infrastructure. The aid provided to individuals will focus largely on temporary housing needs. And a smaller share of funds will be used to mitigate damage from future storms.

For Houston, an Unprecedented Storm but Familiar Impacts

For better or worse, Harris County is well-versed in flood recovery and FEMA’s assistance programs. While certain meteorological characteristics of Hurricane Harvey were unprecedented, setting rainfall records across the affected areas, southeast Texas is no stranger to flood losses.

Harvey is Houston’s third 500-year flood in the past three years. In just the last twelve years hurricanes, severe storms, and floods in Harris County have led to seven major disaster declarations and $1.1 billion in FEMA assistance.

While some of that money went to mitigation measures such as flood control projects and property buyouts, a larger share was used to rebuild public facilities, infrastructure, and homes. Yet, in many cases, structures are not rebuilt to avoid future flood damages and may well need to be rebuilt again. Further, Mr. Trump’s recent decision to revoke the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard—a measure that would have ensured flooded communities rebuilt to be more resilient—means that when the recovery is complete and FEMA leaves, flood-damaged properties may be just as vulnerable as they were on the day Harvey struck.

Both Texas and Florida should use the billions of taxpayer dollars they receive in the coming months to rebuild to higher standards—elevating public facilities and homes well above base flood elevations and buying out or removing repeatedly flooded properties from the floodplain.

As one of the nation’s most thriving and populous cities, and one that has been repeatedly pushed to the brink by catastrophic floods, Houston has an especially unique opportunity to change course and show the country how to rebuild with the future in mind. In doing so, it can become an exemplar of resilience and protect its residents from the damage and devastation they endure today.

This article first appeared on BRINK